Over the past five years, higher education institutions across the country have been using the Engineering for One Planet (EOP) Framework to help transform their engineering curricula. Through their faculty and students, they’ve found innovative ways to instill social and environmental sustainability into their courses, and to broaden EOP’s reach beyond engineering.

Recently, ABET and The Lemelson Foundation recognized one of those faculty innovators with the inaugural Engineering for One Planet Innovation in Sustainability Award. Dr. Jennifer Watt, Director of Sustainability Education at the University of Utah, was recognized for her leadership on sustainability education at her university and for her collaboration with engineering faculty who had been awarded EOP-related grants.

A faculty member’s prior award from the ASEE EOP Mini-Grant Program and an EOP seed grant from The Lemelson Foundation have helped expand sustainability education across the University of Utah’s engineering programs, and Dr. Watt and her colleagues have leveraged these resources to extend sustainability to other programs across the campus as well.

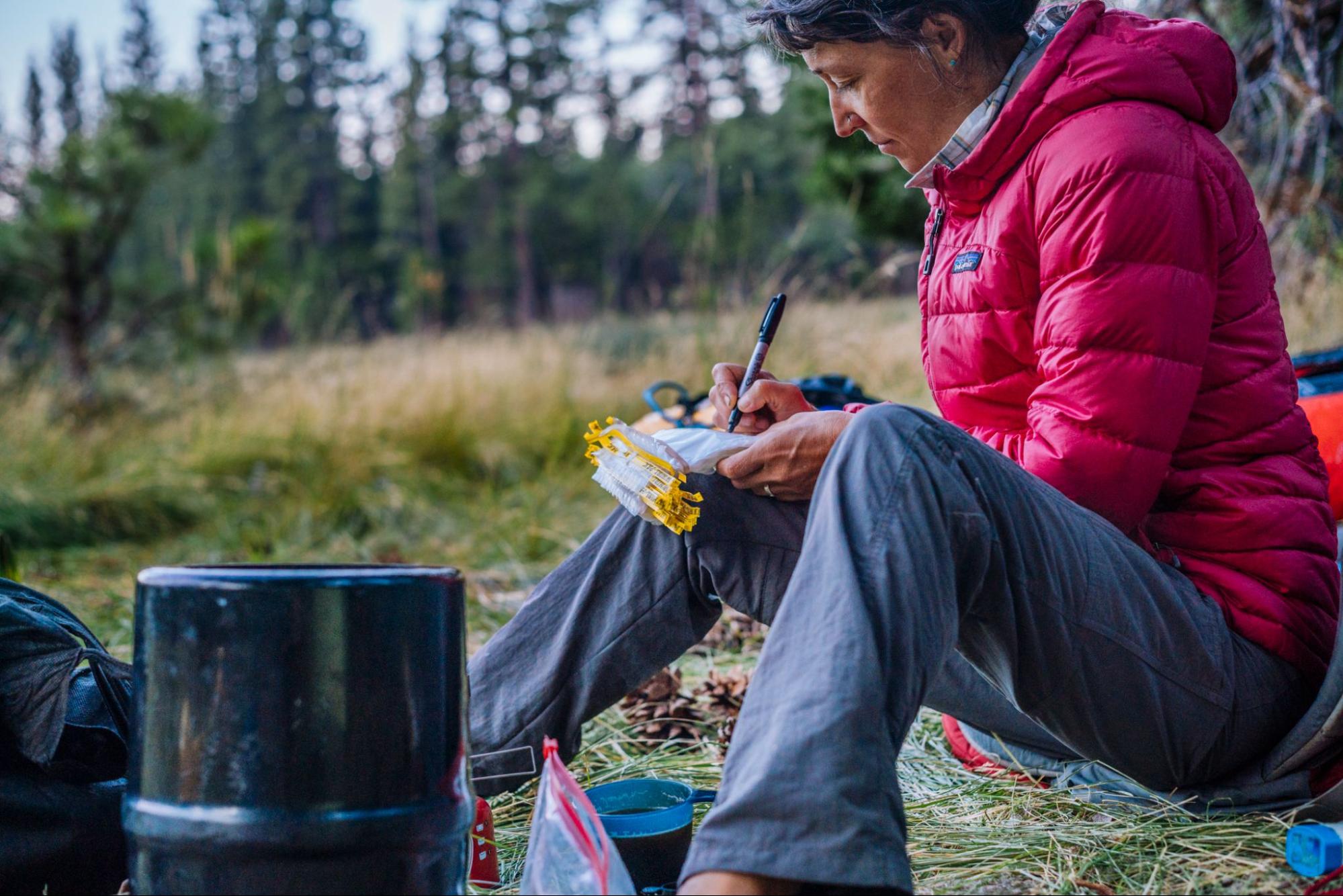

We recently spoke to Dr. Watt, a paleoecologist who studies climate change, about what drives her passion for sustainability — and how the EOP Framework and community have made a difference in her work.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What has been the most important element to the success of your sustainability efforts?

I think that one of the biggest factors is that students want it. Students ask for more sustainability certificates or sustainability courses that relate to their degrees because they want and need to be able to indicate that to future employers. That’s been pretty powerful because the administration hears it louder when the student body says we want this. Positive employment at the end of graduation is an important metric for universities.

The University of Utah’s EOP grant involved integrating sustainability in courses across the engineering college, but also coordinating more holistically with your Office of Sustainability, and assessing student learning outcomes. How did you become involved with this project and what were your findings?

Dave Wagner in the Chemical Engineering department reached out to me when he was writing his EOP grant to ask if I wanted to join and collaborate. They actually have sustainability integrated into every department in our engineering college, but it was motivating to see that they wanted more.

For my project, we did focus groups with engineering students, asking them a series of questions to look at what they truly learned about sustainability and get more qualitative data. And then we took it one step further by conducting focus groups with engineering faculty, asking them what motivates them to integrate sustainability. Because if faculty aren’t motivated to do it, students are not going to get it in a quality way in their courses.

Some faculty initially said they didn’t know the point of it, but by the end of the focus group, their own colleagues had convinced them. We thought that was one of the most useful one-and-a-half hours we’ve spent. The grant was a pilot project to see if you can take this template to other disciplines, and now this year we’re hosting six faculty focus groups in different colleges at the university to compare to the engineering faculty.

How do you measure and evaluate success in sustainability education?

There’s the [AASHE] Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) for universities, and I oversee the education points for our rating. The University of Utah just signed a Climate Action Plan last year with very explicit goals. By 2030, 75% of our students will learn about sustainability in their coursework related to their degree, and by 2040, it’s 100%. I’m responsible for meeting that goal.

What’s your biggest challenge in convincing faculty to integrate sustainability into their courses?

What I have found is that there’s really not resistance to change from faculty, but there’s resistance to additional work. At big, top-tier research universities, very little credit is given to teaching. Your tenure and promotion packets are based almost entirely on research. But in our newly formed School of Environment, Society, and Sustainability at the University of Utah, we will be voting very soon on a measure to make teaching and research equal for our tenure. I think that would make a big difference because then faculty would be rewarded for putting energy into teaching well.

As far as integrating sustainability across campus, it’s really not that hard. The hardest part is meeting the right faculty who are interested. I host a one-day teaching workshop every May, and invite faculty to come with a syllabus for a class. We do all of the work of getting the sustainability content into that class during that day, and that’s been pretty successful. Once I have that one faculty member as an advocate in a department, then I can usually rely on them to help me spread the word.

We now have sustainability integrated into about 65% of the departments and programs on our campus. Just this year we got sustainability into the first-year curricula for all medical students, which was the biggest win.

What other sustainability resources are you providing for faculty?

I’ve developed something from these workshops similar to the EOP Framework that makes it easier for faculty to make curricular change and that can be broadly used across disciplines. It’s a resource page that walks faculty through the process step-by-step.

The biggest barrier I’ve found is that faculty don’t have a lot of time to find additional readings, resources, or lab activities that really integrate sustainability well. And so I did a pilot program two years ago for faculty to receive funding for a grad student to do the actual gathering of whatever they needed, like five hours per week.

Now I’m running that as a small grant program, and that’s how we got sustainability into the medical school — hiring a medical student to literally do the work for faculty that will be used for their own cohort of classmates. These are very small grants, but paired with step-by-step guidance and giving faculty the resources to have someone help them, it’s been very successful.

How important has cross-disciplinary collaboration been to your efforts?

It’s been so valuable because you get stuck in your own head in your individual projects. Dave Wagner introduced me to the EOP Framework and helped me understand how I could use it in other areas. If it were just me in my office working on this without a group of colleagues, I never would have been successful.

And even with the pilot project that we did, I had to bring in other colleagues that had their own expertise, such as running qualitative focus groups. Dave and I would have never gotten there without them because we are very quantitative researchers in our own disciplines.

How would you describe your professional journey?

I did a lot of different things to arrive at this point. I never planned on getting a PhD and going into education. I really thought I would end up working at the Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management at a research station. Doing research was my trajectory, but I ended up teaching at a community college and loving it.

Working with students is what I like the best, and where I feel I can make the biggest difference. I love creating academic programs that are going to help students get jobs they’re passionate about. We need students out in the workforce that have been educated in sustainability because that’s going to be what makes change. It’s not going to be me personally. It’s going to be them. So that’s definitely my bright spot.